Plowden Reminiscences by Ted Lucas, son of the last Plowden stationmaster.

Tom Matthews of Wentnor was in charge of the coal depot at Plowden Station, for W. S. Gwilt. He came to work in a pony and trap. There was a stable for the pony and it used to graze on the land behind the office. Tom was an uncle to Dick Matthews (fireman) whose father, a brother to Tom, was the ganger in charge of the platelayers of the BCR. His name was Ned and he lived up Cwm Head, above Horderley.

Tom was an uncle to Dick Matthews (fireman) whose father, a brother to Tom, was the ganger in charge of the platelayers of the BCR. His name was Ned and he lived up Cwm Head, above Horderley.

For the sheep sales at Craven Arms, an early morning train of truckloads of sheep was run before the normal service. From time to time a GWR tank engine was hired, when one of the BCR engines was out of service, likewise on Shrewsbury Show days a main line large carriage was hired to cope with the extra passengers.

Bishop’s Castle church Sunday school used to come to Plowden for their annual picnic at the foot of the Longmynd. My mother (Fanny Lucas) used to boil the water to make the tea. Mr. Morris of Plowden Hill had bags of wheat that came by rail for him to collect and grind into flour. The mill was run by a water wheel by the River Onny. Many tons of stone from the Squilver Quarry were transported by the BCR from Lydham Heath to Plowden and Horderley, as were trucks of tarmacadam for the County Council from away (Clee Hill I think) to unload. As it was a solid mass in the trucks, a steam-pipe from the traction engine was used to help to remove it from the trucks. It was then loaded into trailers and pulled by the traction engine to wherever it was being laid. Milk churns (17 gallons type) were unloaded at Plowden, I can’t remember who collected them.

A motor bus was also run by the BCR to replace the train at times. One evening it had a puncture outside Plowden Station and the driver (Arthur Hillman), who wore a uniform and peaked cap with B.C.T.C. (Bishop’s Castle Transport Company) across the front, had to change the wheel. On board was a policeman handcuffed to a prisoner being transported to Shrewsbury Gaol. They must have missed the connection at Craven Arms. I have often wondered how they got on.

A motor bus was also run by the BCR to replace the train at times. One evening it had a puncture outside Plowden Station and the driver (Arthur Hillman), who wore a uniform and peaked cap with B.C.T.C. (Bishop’s Castle Transport Company) across the front, had to change the wheel. On board was a policeman handcuffed to a prisoner being transported to Shrewsbury Gaol. They must have missed the connection at Craven Arms. I have often wondered how they got on.

On one occasion the train became derailed at Hillend between Plowden and Horderley owing to the state of the track (at that time the real sleepers were rotting away and being replaced by green wooden sleepers cut from felled trees), anyway the train still on the line was uncoupled and went on to Bishop’s Castle, returning later with all the labour that could be mustered. With hand-worked jacks (there were no mobile cranes) and after a lot of very hard work the trucks were back on the rails, the track repaired as best they could and the train away home to Bishop’s Castle. In the whinberry season my father (Will Lucas) used to buy the fruit picked by people on the Longmynd then package it and send it to a dye works in Blackburn.

Jabez Barker of Shrewsbury (timber merchants) felled a lot of timber at Myndtown, at the foot of the Longmynd. A traction engine was used to winch and load the timber onto the timber carriages, but shire horses pulled the carriages down alongside the Longmynd to Plowden Station where it was worked onto railway timber wagons (using the crane) and transported away to Shrewsbury. The horses by the way were stabled at Mr. Davies’ Folly Farm between Plowden and Lydbury North. In my schooldays at Plowden the BCR was a busy line, but towards the end of the 1920’s it started to decline and never got on its feet again.

Jack Bedell MBE

Being the son of a Grocer and Farmer I saw and enjoyed much of the Bishop’s Castle Railway, at that time my father kept horses for deliveries and collection of goods. I well remember riding on the Horse Dray to the Goods Shed where a daily collection was made of various goods that had arrived in one of the BCR goods vans. In this would be goods for traders in the town, most being delivered to the shops by Vaughans’ horse cart. My father was very much involved in the corn trade, selling direct to farmers who would collect various feeding stuffs direct from the station by wagon and horses. The vans containing the corn etc. would be on a short length of line from the Goods Shed to buffers at the back of the station building.

In this would be goods for traders in the town, most being delivered to the shops by Vaughans’ horse cart. My father was very much involved in the corn trade, selling direct to farmers who would collect various feeding stuffs direct from the station by wagon and horses. The vans containing the corn etc. would be on a short length of line from the Goods Shed to buffers at the back of the station building.

Farmers would also collect wagonloads of coal at the beginning of winter from the Beddoes and Gwilt Depot at the station. These two coal merchants delivered coal around the town in horses and carts.

Monday was very much a commercial traveller’s day for visiting Bishop’s Castle; they would arrive on the mid-day train, and leave on the evening train back to Craven Arms. I well remember two particular travellers who saved their cigarette cards for me, and I would rush to the train to meet them.

Attached to the train every alternate Monday would be one or two cattle trucks conveying farmers’ sheep and cattle to Craven Arms market. In the trucks there was a partition, sheep probably behind the partition and cattle in the main body of the truck. These animals were loaded in the pens situated near the timber dock. Returning on the last train from Craven Arms on these Mondays would be the local butchers’ purchases of cattle and sheep for their trade. These animals would be unloaded on the passenger platform after the passengers had departed. They would be then driven to the various slaughterhouses in the town.

Two special sheep trains were run to Craven Arms in September for special sales. These trains left Bishop’s Castle at 6 a.m., loading in the cattle dock. They probably had three or so wagons from Bishop’s Castle, and picking up en route to Craven Arms at Lydham Heath, Eaton and Plowden. The shepherds in charge of the sheep travelled in the Guard’s van with their dogs, and dogfights were not unknown. Special Trains for the Sheep Sales and March & October Cattle Sales would leave Bishop’s Castle when trainloads could be made up. Any remaining wagons were then forwarded with the normal service. My father often bought cattle at Shrewsbury and other centres and these would be loaded to arrive at Craven Arms during the night, and then up on the first train in the morning.

From the sheep sales at Craven Arms local farmers would often buy the odd ram, and these would be transported in the passenger guard’s van with other goods.

The transport of large timber, whole trees etc. was much of the railway business. I remember a couple of persons who had horse drawn timber wagons to transport the timber from the woods to the station, one was a man named Jack Eggiston who stabled his horses at the Six Bells. I well remember as a small boy returning from the High School at 3.30 p.m. to see two timber wagons, three horses at each, drawn up outside the pub, and the Waggoner’s enjoying their pints.

T.R.Perkins February 19th 1934

On Thursday week a friend of mine and I motored to Minsterley by way of Craven Arms and Lydham, so we had a good look at the BCR en route. “Carlisle” was working the train – one coach only, the L.S.W.R 6 wheeler and a few goods wagons- and looked quite smart, very clean and all the brass work polished. Alas! All else was otherwise, the track is getting positively unsafe: the engine bends the rails as it passes, and half the sleepers are rotten, bolts sticking out 2inches or so.

We went down to Bishop’s Castle and had a look round: one of the old coaches that had the chain brake is now a motor shed!

Extract from "A Tale Of Two Houses"

We were given permission by Lady More to reprint an extract from the book ” A Tale of Two Houses” which was published by Sir Jasper More in 1978.

“Then back to the station, to rescue the luggage, and to the train destined to become so familiar, standing in the bay. “Passengers are requested not to throw out of the window anything likely to injure men working on the line”, said a notice in the compartment. Above the seats would be photographs of strange mysterious places; Kenilworth, Llandrindod Wells, The Mumbles. The whistle would blow and Aunt Dorothy would wave goodbye. We were on our way.

Past Condover, past Dorrington, past Leebotwood and then the climb up into the South Shropshire Hills, once seen never forgotten. Our excitement would rise: soon we knew the names; on the left the Lawley and Caradoc, on the right the Longmynd, and in two minutes we would be drawing up at the nerve centre Church Stretton. Then down the hill to Marshbrook, and the great event of the day, the station at Craven Arms. Once we decanted ourselves and our luggage, we rushed over the bridge, and there standing in the bay was our special favourite, the Bishop’s Castle train.

The Bishop’s Castle train, even to our youthful eyes, was not like other trains. It was not even like other railways, for it was a railway on its own, the Bishop’s Castle Railway. It had started – so we came to learn – in the 1860’s and partly under More auspices, with the double purpose of providing rail connection between our local town of Bishop’s Castle and the outside world. As happened not infrequently where the More family was concerned, the money ran out, the first object was abandoned and the enterprise focused on Bishop’s Castle. It was nine miles of single track with five intermediate stations. The landowners had not been paid, the company went bankrupt and thereafter spent the rest of its corporate life in Chancery. Occasionally landowners would get restive, and men would be employed to interrupt the service by removing the rails. The company would retaliate with a double gang, one gang to decoy the landlords’ men to drinks in the nearest pub, the other to put back the rails to let the train through. Eventually this was thought to be precarious and the landowners were bought out by the Bishop’s Castle Railway Defence Trust to which my father had to contribute five hundred pounds.

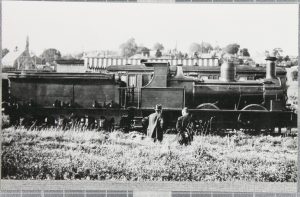

There were two engines, ‘Carlisle’ and ‘No. 1’, and we would look eagerly to see which was heading the train today.was small, but ‘Carlisle’, built in 1865, was a largish engine with tender and we soon got to know that Whitaker would let us onto the footplate. (Once, in the 1914-18 War we did the footplate journey in the company of eighteen very large Australian soldiers).

No 1′ Mademoiselle and the luggage would have to find a carriage. As the carriages were successively condemned, the ‘receiver’, who ran the railway, would buy up job lots and you never knew if you would be travelling in something from the Brecon & Merthyr, the London & South Western, or the Cockermouth Keswick & Penrith. The whistle would go, Whitaker would show us how to swing over the regulator and we would be away.

The first station, Stretford Bridge Junction, was one of our favourites. It had no station nameplate, just a platform with two metal advertisements for Mazawattee Tea and Bibby’s Foods, and it could only be approached by trespassing across a farmer’s field. Horderley, Plowden and Eaton were grander, each with a red brick station house. We would begin to thread our way up the railway’s magical valley with sonorous rumbling as we negotiated bridge after bridge over the River Onny.

Horderley, Plowden and Eaton were grander, each with a red brick station house. We would begin to thread our way up the railway’s magical valley with sonorous rumbling as we negotiated bridge after bridge over the River Onny.

At Plowden was a road bridge built of transverse timbers with gaps in between; it was here, on one of our journeys, that we sighted a cow with all four legs fallen through the gaps and its horns waving over the line; Cadwallader (the guard) had had to pull it by the horns with main force while the station master sat on its head and Whitaker slowly drew the coaches past. Eaton had no stationmaster but was looked after by Mrs Bason, a station mistress of character who, if there were no waiting passengers, would signal the train through at walking pace. Newspapers and packets would be thrown out by Cadwallader onto the platform while any more fragile parcels would be carefully lobbed into Mrs Bason’s out-stretched skirt. The next station would be Lydham Heath.

From Eaton onwards we finished the magical valley and launched into an expanse of open country, beyond which we would see the Linley skyline. Excitement mounted; the hills we got to know so well; on the left Heathmynd, then Rhadley and Linley Hill; and then on the right the dramatic landmark of the Beech Avenue curling over the top of Norbury. Somewhere short of these hills was our destination, the Cottage.

Lydham Heath was as far as the railway had managed to get on its way to Wales. It now formed a terminus and for the final two miles to Bishop’s Castle the train had to reverse. This meant all trains had to stop and, as Lydham Heath was our station, this was all to the good. It consisted of a short platform, a tin shack, and a set of buffers up against the hedge, which bordered the main road.  This was the branch line station from which, in time long past, my grandfather’s forgotten London guests had had to be retrieved. There was no house in sight; no form of transport; indeed hardly any road traffic. In railway terms there were awkwardnesses; all trains had to include goods and cattle as well as passengers; sometimes it would be the cattle rather than the passengers who finished up opposite the Lydham Heath platform; and in my grandmother’s day, Cadwallader had had on occasions to shout in broadest Shropshire to the driver; ‘hitch up the train a bit, Harry. Mrs More canna’ get in’. But none of these problems were ours. For there waiting on the platform, would be our ever-reliable guide, philosopher and friend, Sam Davies.

This was the branch line station from which, in time long past, my grandfather’s forgotten London guests had had to be retrieved. There was no house in sight; no form of transport; indeed hardly any road traffic. In railway terms there were awkwardnesses; all trains had to include goods and cattle as well as passengers; sometimes it would be the cattle rather than the passengers who finished up opposite the Lydham Heath platform; and in my grandmother’s day, Cadwallader had had on occasions to shout in broadest Shropshire to the driver; ‘hitch up the train a bit, Harry. Mrs More canna’ get in’. But none of these problems were ours. For there waiting on the platform, would be our ever-reliable guide, philosopher and friend, Sam Davies.

The important part of Sam’s equipment today would be the wheelbarrow. While Whitaker was manoeuvring ‘Carlisle’ to the far end of the train for the last two miles to Bishop’s Castle, Sam would be loading the luggage. The luggage made a sort of mountain in the barrow, and some of it would have to be lashed to the sides with ropes. A farewell wave to Whitaker and off we would all set, pacing the wheelbarrow with Sam.”